Rapidly rising inflation numbers reported in recent months could be the first domino to fall in letting some air out of the pandemic housing boom.

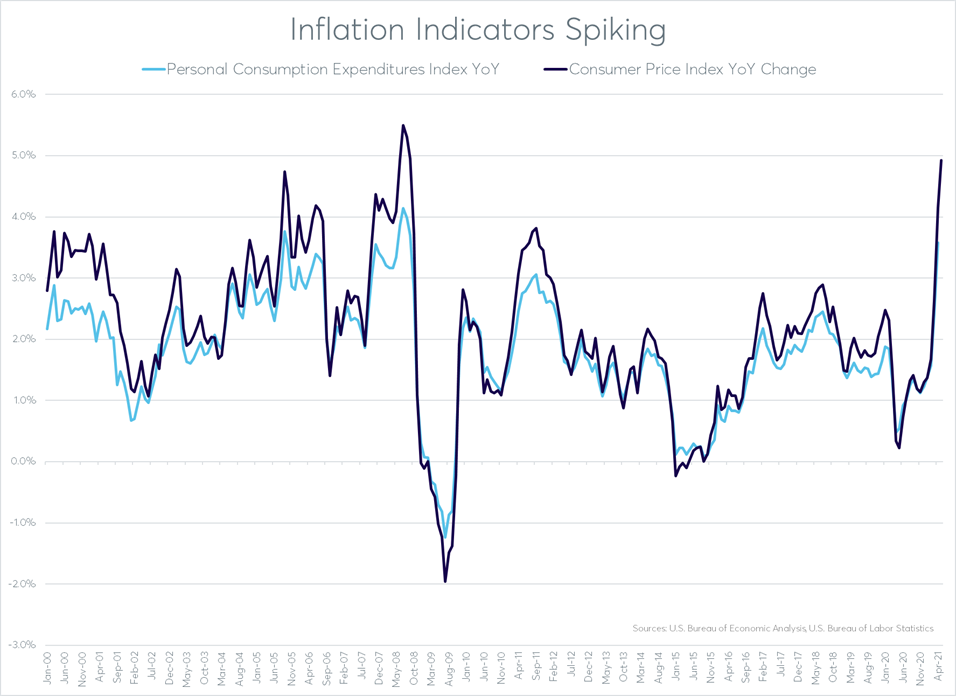

Two important inflation measures spiked to the highest level since September 2008 — a more than 12-year high. The consumer price index (CPI) jumped a higher-than-expected 4.9 percent in May compared to a year ago, and the personal consumption expenditures index (PCE) also beat expectations, rising 3.6 percent on year-over-year basis in April.

For the CPI metric, May represented the third consecutive month with a more than 2 percent annual increase. That 2 percent threshold is important because Federal Reserve Board has said it’s aiming “to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent over time” with its various monetary policies — including its setting of the federal funds rate, which indirectly influences mortgage .

Given this 2 percent target, sustained average inflation above 2 percent would likely trigger policy adjustments by the Fed — including potentially a raising of the federal funds rate — in an effort to contain the negative economic impacts of inflation. Even with the recent jumps, the 12-month trailing average for both inflation indexes are still below the 2 percent threshold: 1.9 percent for the CPI and 1.5 percent for the PCE index. But in its most recent statement released on June 16, the Federal Open Market Committee raised its inflation expectations for 2021 to 3.4 percent, a percentage point higher than its previous projection in March.

The Fed has stated that the PCE index is the inflation metric it tracks most closely. A closer look at that index reveals an even more startling high inflation watermark. When excluding more volatile food and energy prices, that index was up 3.1 percent in April. That was the biggest increase since July 1992, a nearly 29-year high. Similarly, the CPI excluding food and energy prices increased to a 29-year high of 3.8 percent in May.

Transitory or Troubling?

Many economists and the Fed itself are referring to the spring 2021 inflation jump as transitory in nature. They argue the root causes driving the inflation increase — namely government-stimulated demand combined with supply chain disruptions — are temporary in nature. As the pandemic fades, government stimulus money will dry up and supply chains will be restored.

But others, including Warren Buffet and Deutsche Bank economists in a recent white paper, see more ominous signs of a longer-term inflation issue.

“Even if some of the transitory inflation ebbs away, we believe price growth will regain significant momentum as the economy overheats in 2022. Yet we worry that in its new inflation averaging framework, the Fed will be too slow to damp the rising inflation pressures effectively,” write the report’s authors, which include Deutsche Bank’s chief economist David Folkerts-Landau. “The consequence of delay will be greater disruption of economic and financial activity than would be otherwise be the case when the Fed does finally act. In turn, this could create a significant recession and set off a chain of financial distress around the world, particularly in emerging markets.”

If these admittedly contrarian predictions hold true, the housing market may be in for a downturn resulting from larger economic forces than the housing supply-demand imbalance that has been driving the pandemic real estate rally.

Pressure Release Valve for Home Prices

But if the Fed responds more quickly to the recent spike in inflation — rather than waiting for inflation to average 2 percent over time — it could as a pressure release valve for rapidly rising home prices. because two of the Fed’s primary actions for combatting inflation would likely put upward pressure on mortgage rates: decreasing its bond-buying program of at least $80 billion in Treasury securities and $40 billion in agency mortgage-backed securities per month; and raising its target for the federal funds rate.

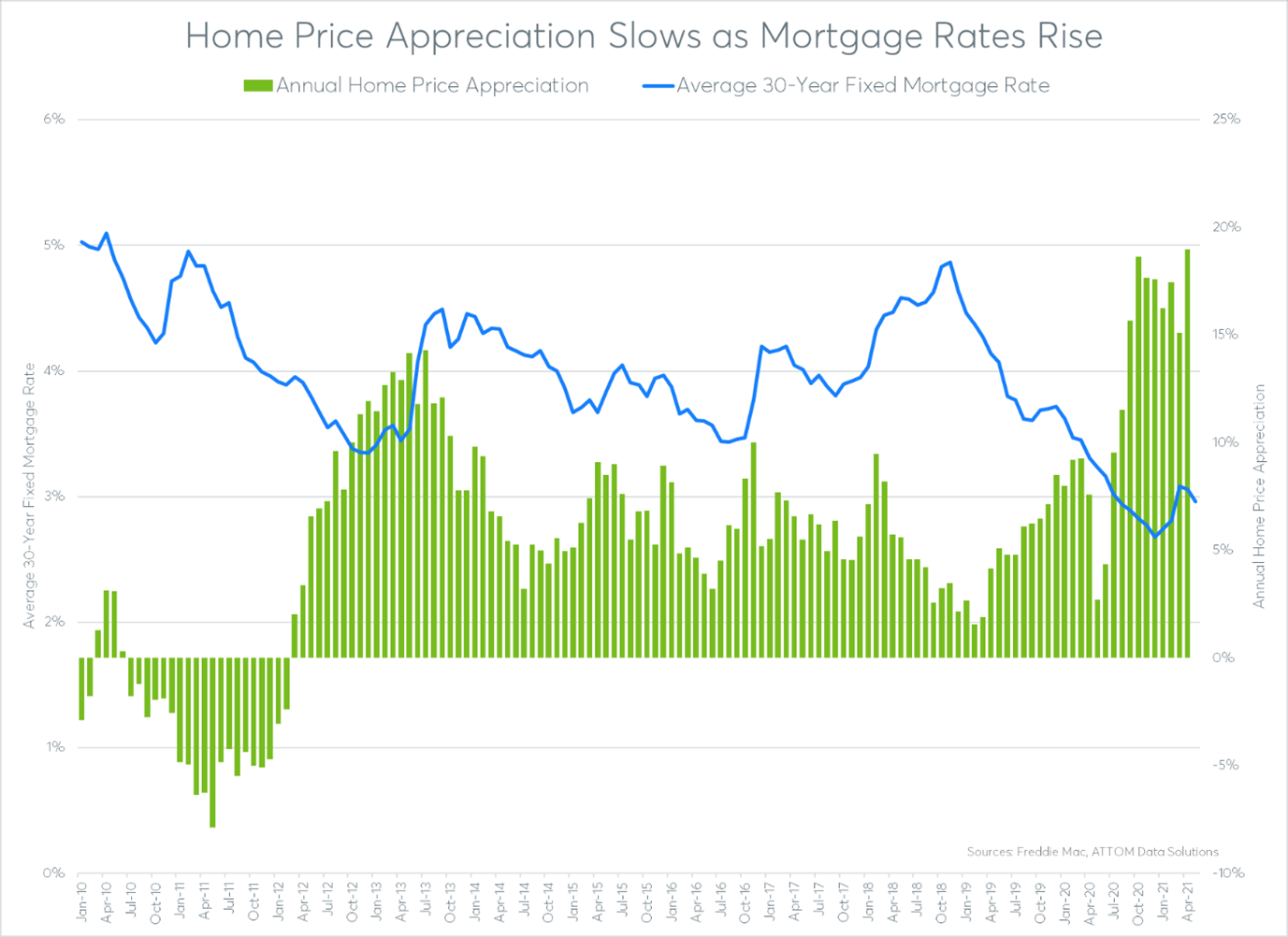

We’ve seen a similar pattern of rising mortgage rates and cooling demand twice in the last seven years: in 2013 and 2014, and again in 2018 and 2019.

In 2013, with housing demand bouncing back strongly after home prices bottomed out the year before, annual home price appreciation rose to a new post-Great Recession high of 14.3 percent in July, according to median home price data from ATTOM Data Solutions. But the average 30-year fixed mortgage rate rose above 4 percent in June and continued above 4 percent for 18 consecutive months. During that period, home price appreciation pulled back to as low as 4.4 percent in October 2014

Home price appreciation began to flirt with the double digits again in early 2018, hitting as high as 9.5 percent in January. But rising mortgage rates once again cooled demand, slowing appreciation. Average mortgage rates rose above 4 percent in January and continued to rise — driven in part by five consecutive quarterly increases in the Fed’s federal funds rate target from Q4 2017 to Q4 2018 — and reached as high as 4.87 percent in November 2018. A few months later in February 2019, home price appreciation dropped to seven-year low of 1.6 percent.

A similar scenario could play out late this year and into 2022 if the Fed raises its federal funds rate target more quickly in response to the recent inflationary pressures. This would most likely cool demand for housing and slow the torrid price of appreciation. Given the chronically low supply of housing inventory; however, that scenario most likely wouldn’t result in a bursting housing bubble. It would simply let some air out of the home price balloon, making it less susceptible to bursting when another sharp object (like a recession caused by more persistent inflation for instance) intersects with its flight path at some point in the future.